After justices warned of prolonged suffocation, Alabama subjected Anthony Boyd to the longest nitrogen execution in U.S. history.

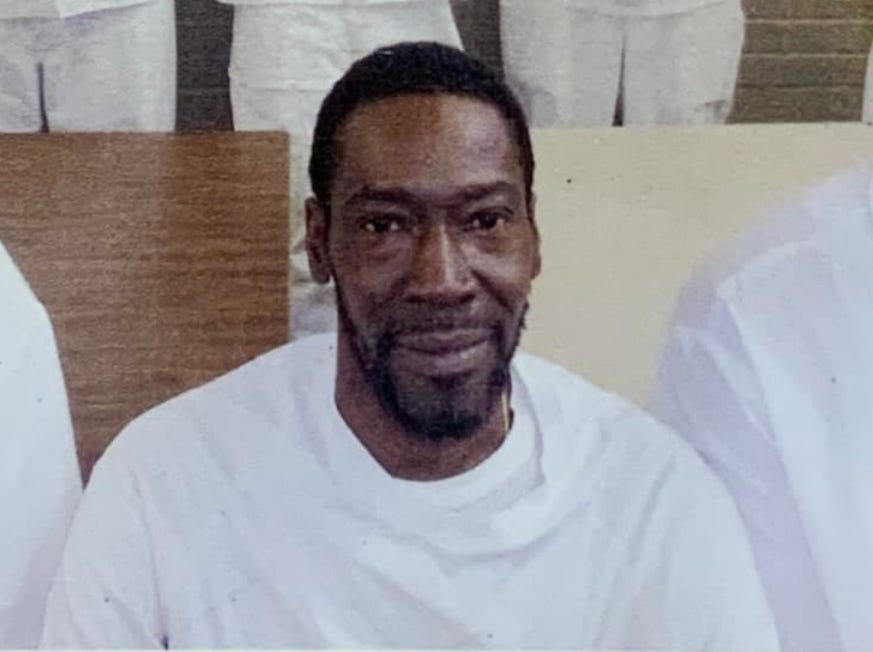

Boyd was the chairman of Project Hope, a death row-led nonprofit. Its members are left reeling in the wake of their leader's suffocation execution.

Because of a failure by the nation’s highest court to enforce the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, the experiment continues.

That was the conclusion of three U.S. Supreme Court justices—Sotomayor, Kagan and Jackson—who wrote a stinging dissent Thursday explaining why they would have allowed Anthony Boyd, a condemned Alabama man, a stay of execution to challenge the method the state would use to kill him: suffocation through the use of a nitrogen gas mask.

“Allowing the nitrogen hypoxia experiment to continue despite mounting and unbroken evidence that it violates the Constitution by inflicting unnecessary suffering fails to ‘protec[t] [the] dignity’ of ‘the Nation we have been, the Nation we are, and the Nation we aspire to be,’” the Court’s minority wrote. “Seven people have already been subjected to this cruel form of execution. The Court should not allow Boyd to become the eighth.”

A majority of the Supreme Court, who chose not to provide reasons for their decision, disagreed.

So in Alabama, among the lonely southern pines and freshly baled cotton, the dissent fell on deaf ears. Alabama prison officials showed the world “the Nation we are.” Boyd became the eighth.

Thursday evening, Alabama executed Anthony “Ant” Boyd, who maintained his innocence, by nitrogen suffocation.

The court’s dissenting justices had speculated that Boyd would be deprived of oxygen while conscious for two to four minutes before gasping for air, thrashing against his restraints, and being subjected to “psychological torment” until he was declared dead around twenty minutes later.

A little over an hour after their opinion was issued, Alabama began conducting what would become the longest nitrogen suffocation execution in the method’s history, exceeding even the worst expectations of the court’s minority.

At 5:50, correctional officers clad in blue, their name tags removed, opened the curtains of the death chamber to begin the state’s grim orchestration. Before those curtains would close about 37 minutes later, Boyd would gasp for air inside the gas mask more than 225 times.

When the curtains opened, Boyd gestured toward his brother, sitting just on the other side of the witness glass wearing a black tee shirt featuring Bible verses including Psalm 23, “The Lord is my Shepherd.”

The prison’s warden, Terry Raybon, read Boyd’s death warrant and asked if he had any last words.

Boyd, strapped to a gurney with a transparent gas mask attached to his face, spoke out for the last time.

“I didn’t kill anybody. I didn’t participate in killing anybody,” he said. “There is no justice in this state. It’s all political. It’s revenge motivated. It’s not about closure, because closure comes from within, not with an execution. There will be no justice in this state until we change this system. I want all my people to keep fighting. Let’s get it.”

About 5:54, the warden exited the small, austere death chamber, its bare fluorescent lights illuminating Boyd’s Black body, wrapped in a white cotton sheet, below.

At 5:55, a guard appeared to check for leaks in the gas mask’s seal.

Just after, another guard’s radio squawked and the process lurched forward.

Rev. Jeff Hood, Boyd’s spiritual advisor, stepped toward Boyd from the corner of the chamber just a few feet away and held the condemned man’s hand.

Hood, a slim, bald, bearded man wearing glasses and a suit over his religious frock, drew the sign of the cross in the air above Boyd.

Around that time, Hood began to move back toward the wall but stopped. He appeared surprised and moved back toward Boyd. One journalist stood up to attempt to see around Hood, who was now standing between Boyd and the witness glass.

“Ma’am, we need you to have a seat,” a guard said.

She complied, a “stay seated and quiet” sign—a car tag from the prison’s license plate facility—mounted in the concrete wall above her head.

Hood opened his Bible at Boyd’s side and appeared to begin reading aloud.

Around 5:57, as Hood continued to read, Boyd began to violently react, thrashing against his restraints. His eyes rolled back, leaving only their whites, the color of the sheet. Boyd continued to convulse for at least a minute, shaking back and forth and lifting his legs from the gurney.

By 6:00, Boyd’s movement had slowed. Hood signed the cross once again.

Around 6:01, Hood moved back toward the wall and a prison guard leaned down over Boyd for several seconds. Boyd was still visibly moving during what may have been a consciousness check.

Around that time, Boyd began a series of deep, agonized breaths that lasted for more than 15 minutes, each break shuddering Boyd’s restrained head and neck.

One gasp after another. Minute after minute. You could hear reporters begin marking the breaths in their notes, the pencil scribbles audible in the air.

Gasp. Scribble. Gasp. Scribble.

After about 75 gasps, Boyd’s brother sighed deeply.

Then he broke the silence in the witness room, disobeying the crude directive posted overhead.

“It’s like he’s gasping for air,” Boyd’s brother said, shaking his head.

The gasping continued for another nearly 10 minutes, breath after breath after breath.

6:09. 6:10. 6:11. A small digital clock on the wall above Boyd counts the seconds.

By 6:12, Boyd’s gasps and become more shallow but increased in pace. Around 6:15, he exhaled and his head tilted to the side, away from media witnesses.

At 6:16, Boyd drew another deep breath. Hood once again signed the cross.

Beginning around 6:17, Boyd’s movement was limited. There appeared to be no movement after around 6:20.

Then, minute after minute, the witnesses watched as Boyd lay on the gurney motionless. Boyd’s brother put his head in his hands.

Around 6:27, the correctional officers, expressionless, closed the brown-blue curtains. The state’s performance was over.

Minutes later, a prison spokeswoman said Boyd’s official time of death was 6:33 p.m.

After the execution, Alabama’s prisons commissioner John Hamm said that while the execution was slightly longer than previous ones, the procedure went as planned.

“It was within the protocol, but it has been the longest,” Hamm said.

Hamm could not confirm the length of time nitrogen was flowing into the mask strapped to Boyd’s head.

Moments after Hamm’s remarks, Hood, the spiritual adviser, told members of the press that he believes Boyd’s nitrogen execution was “the worst yet” using the method.

He believes that Boyd was conscious and being tortured for about 16 minutes, a delay he said may have been caused by a faulty seal on the gas mask.

“I don’t think the mask was on correctly,” Hood said minutes after the execution. “There was a gap in the lip of the nitrogen mask that wasn’t there in before in previous executions,” Hood said.

Hood said that during the execution, he was directed by a correctional officer to remain standing by Boyd as the execution proceeded, something that he said was different from previous executions.

“I think it’s possible I was used to block y’all’s view,” Hood told media.

Ultimately, Hood said Boyd’s execution confirms Alabama is unable to safely or constitutionally carry out nitrogen gas executions.

“Alabama is absolutely incompetent,” he said.

Death of a Chairman

Boyd was a leader on death row, mentoring other incarcerated men and guiding Project Hope to Abolish the Death Penalty, a death-row led nonprofit, as its chairman.

His final message in its newsletter, On Wings of Hope, was one of resilience.

“Society has deemed itself better than death row inmates but Society is not acting better than death row inmates,” he wrote in part. “We are not outnumbered. We are not organized. Keep fighting and keep Hope alive.”

For those on living on Holman’s death row, it’s hard to feel like Boyd’s execution isn’t the death of Hope.

Still, they rise.

“The fight continues in your name amongst many,” his brothers on death row wrote just before his death, in a tribute published by Tread. “Do we still have the heart to go on? Yes, plenty! I know what change is, because i saw it in you. Project Hope to Abolish the Death Penalty—we still got work to do.”

Boyd’s execution by nitrogen gas is one of only a handful that have ever been carried out in the United States, primarily in Alabama, which first used the novel method in 2024 when state correctional officials suffocated Kenneth Smith.

The method has been controversial from its inception. Eyewitness accounts, including on Tread, have described violent, protracted executions that have contradicted state accounts and narratives in court filings, which have referred to the executions as “textbook.”

In its dissent’s opening, three of the nation’s top judges asked Americans to get our their phones, start a timer, and just sit for a few minutes.

“Now imagine for that entire time, you are suffocating,” the justices wrote. “You want to breathe; you have to breathe. But you are strapped to a gurney with a mask on your face pumping your lungs with nitrogen gas. Your mind knows that the gas will kill you. But your body keeps telling you to breathe. That is what awaits Anthony Boyd tonight.”

That process, they wrote, amounts to “psychological torment” and is forbidden by the Constitution.

On Thursday night, Alabama exceeded the minority’s grimmest predictions.

Alabama’s nitrogen gas experimentation is not expected to slow. State officials have already begun seeking death dates for additional men on the row.

This is inhumane torture. I have no words except to wonder why we as Alabamians accept such barbarity.

This is absolutely grotesque and we should do everything in our power to stop this madness. Thank you, dear Lee, for being the one who accepts this assignment every time. Please take care of your self.