Alabama plans to gas condemned citizens. Are others already at risk?

With nitrogen gas executions, Alabama plans to go where no state has gone before. Is it already putting innocent people in harm's way?

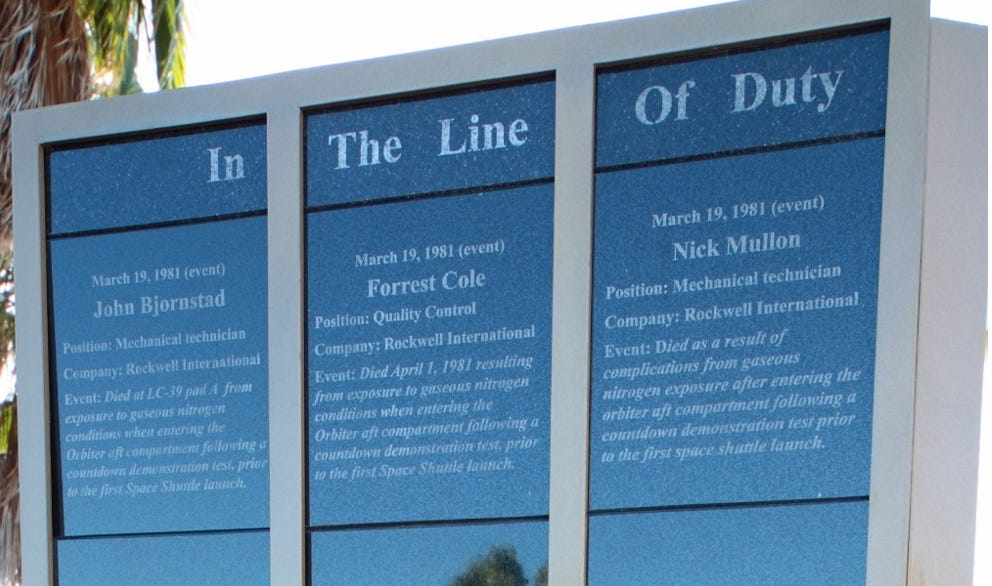

They died in the line of duty.

John Bjornstad and Forrest Cole, technicians working for a NASA contractor, had entered a compartment on the Space Shuttle Columbia for inspections, unaware that nitrogen, a colorless, odorless gas, continued to push the air out of the area where they stood. Deprived of the oxygen needed to survive, the two men collapsed almost immediately, a federal report later concluded.

Then, one after the other, their rescuers became victims, too. Bill Wolford entered Columbia’s aft compartment just a few moments after Bjornstad and Cole. He, too, dropped to his knees, darkness overwhelming him.

Minutes later, Jimmy Harper arrived and saw Wolford’s body draped over Bjornstad’s. Struggling to free him, Harper quickly fell unconscious.

Then came Nick Mullon. He, along with two other workers, arrived and worked to pull as many men to safety as they could.

John Bjornstad and Forrest Cole would not survive their workplace exposure to nitrogen gas. They would be Columbia’s first losses.

Mullon, who had helped save Wolford and Harper’s lives, suffered severe injuries that would take his life years later.

After the men’s workplace deaths, federal agencies including the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and NASA launched comprehensive investigations into what had gone wrong that day in March 1981. Months later, a nearly 500-page report outlined the mistakes, mishaps, and miscommunications that led to the tragedy.

Bjornstad, Cole, and Mullon died in service of an inspired mission — a pursuit aimed at moving mankind forward, one giant leap at a time.

Now, more than four decades after the men’s nitrogen deaths inside Columbia, the State of Alabama is preparing to go where no state has gone before. But does its pursuit of a more grim mission — the taking of a condemned man’s life using nitrogen gas — come at the risk of others?

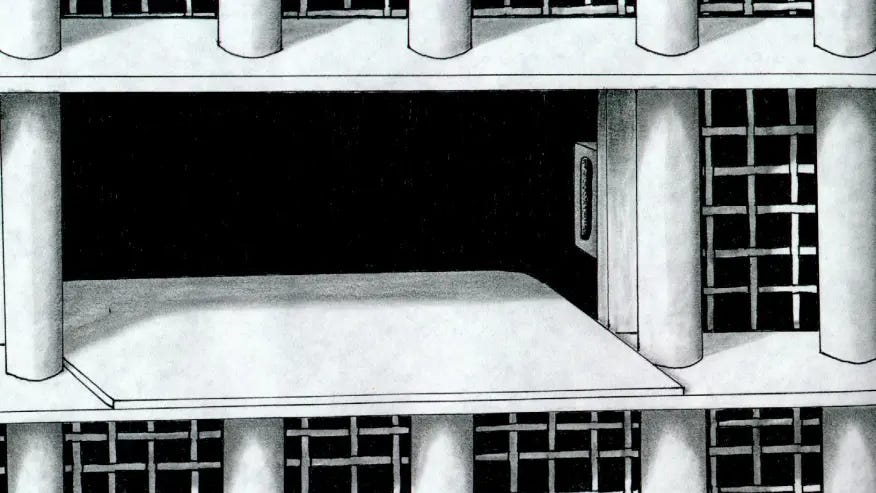

Soon, potentially within weeks, Alabama plans to begin executing its citizens using nitrogen gas. The method is untested, having never been systematically used for judicially-sanctioned executions. The storage and use of nitrogen gas, lawyers for the state have acknowledged, is risky, posing potentially fatal hazards not only to the state’s intended victim, but also to prison workers, spiritual advisors, members of the press, and other incarcerated individuals.

So far, however, officials with the Alabama Department of Corrections have refused to answer questions about the process the agency’s workers will use to gas condemned individuals, including inquiries about precautions taken to protect staff, witnesses, and others present. But unlike the accident aboard Columbia, which was subject to federal workplace oversight, state-run facilities like prisons operate in a regulatory vacuum in many jurisdictions, including Alabama, compounding the risk of an untested method of execution that may already place workers at risk of injury or death.

The storage and planned use of nitrogen gas by the State of Alabama to kill its citizens, despite the admitted risks involved, is not subject to any workplace regulator, state and federal officials confirmed to Tread this week.

The night the gas came

He remembers the night the gas came.

The man, a resident of Alabama’s death row, watched as a truck backed up inside the gates of Holman Correctional Facility in Atmore. Night had already fallen across south Alabama, but the prison yard’s tired, mustard yellow lights reflected off the gas tanks as the switch took place.

The exchange came after Airgas, a major industrial gas supplier, announced it would not allow its nitrogen to be used in the executions of condemned citizens in the Heart of Dixie.

So out with the old. In with the new.

That night in early 2023, workers placed the new, tanks, seven or eight dark-colored cylinders, into a small storage room next to the building that houses Alabama’s execution chamber, the man explained.

The gas tanks’ arrival at Holman was met with anxiety and dread. Many of the men on death row saw the move, of course, as a sign the state was one step closer to the implementation of their deaths.

And everyone can tell there are risks involved with moving the process forward, he said. The storage room where they placed the tanks is only about twenty feet from an air intake for the main facility, he explained.

“That part is disturbing,” he said.

How we got here

As legal challenges, logistical difficulties, and botched executions plagued the implementation of lethal injections in states across the country, Alabama lawmakers approved the use of executions by nitrogen gas in 2018. Legislators in the Yellowhammer State followed the lead of Oklahoma and Mississippi, the only other states to have authorized the method of execution.

In Oklahoma, Republican State Rep. Mike Christian had introduced the nation’s first law providing for nitrogen executions after watching a BBC documentary called How to Kill a Human Being — a film produced by a conservative former member of parliament in a country where the last state executions took place in the 1960s.

Alabama’s legislation approving the method allowed condemned individuals a 30-day period to “opt into” execution by nitrogen suffocation. During that time, dozens of men notified officials that they preferred the method in the face of the state’s lethal injection protocol.

That protocol has come under intense scrutiny in recent years, particularly after Alabama botched three consecutive attempts at executions: the lethal injection of Joe Nathan James, which led to his death, and the attempted lethal injections of Alan Miller and Kenny Smith. Both Miller and Smith survived the state’s attempts to kill them.

Those failures led to a brief moratorium on state-sanctioned deaths while its Department of Corrections conducted a review of its execution process. But months later, the in-house review, widely criticized as lacking rigor and independence, led to no substantive reforms of the death penalty system. Instead, the state chose to increase the window of time allowed for executions to be carried out and limited reviews of “plain errors” in capital cases.

Now, on July 21, James Barber is scheduled to be the first man put to death by Alabama since the end of the three-month execution moratorium. Barber, who was convicted of the 2001 murder of Dorothy Epps, has asked a federal court to forbid the state from executing him by any method but nitrogen hypoxia.

In a statement sent to Tread, a representative of ADOC said the department has “completed many of the preparations necessary for conducting execution by nitrogen hypoxia” but that “the protocol, however, is not yet complete.”

The department did not answer questions regarding safety protocols or training around the storage and planned use of nitrogen at Holman.

After Columbia

Long after Columbia, there was John Ferguson.

The 29-year-old contractor at a Delaware oil refinery had been trying to retrieve a roll of duct tape from inside a reactor he was repairing when he passed out, asphyxiated by nitrogen inside the tank that his employer had failed to adequately warn him about, according to a federal investigation.

Then John Lattanzi, 57, came to help.

The crew foreman, Lattanzi jumped to his coworkers’ aid, a witness said, quickly placing a ladder into the reactor to aid in retrieving Ferguson. Moments later, Lattanzi had collapsed, too, unaware that nitrogen gas had replaced the oxygen around them.

John Ferguson and John Lattanzi both died from asphyxiation due to their exposure to nitrogen gas, autopsies would later conclude.

Nitrogen deaths in U.S. workplaces have been a known hazard for decades. In 2003, the U.S. Chemical Safety Board issued a safety bulletin about the dangers of nitrogen in the workplace that analyzed federal data on workplace accidents.

In the decade leading up to the report, the agency cited at least 85 nitrogen-related incidents — an average of 8 deaths and 5 injuries every year in the United States.

Because nitrogen can’t be seen or smelled, the safety bulletin warned, the gas poses a particular risk to humans, which may not be aware of the toxic environment until it is too late. Because nitrogen makes up most of the air we breathe, regulators point out, the gas may seem harmless. But some forms of the chemical — like the compressed gas held in tanks — can quickly displace oxygen needed to breathe, becoming a fatal hazard.

As nitrogen spreads through the air, it can displace the oxygen needed to breathe. The air we breathe is around 21 percent oxygen. If that number dips below 16 percent, a human may begin to experience increased pulse, impaired thinking, and reduced coordination, according to the report. At about 12.5 percent oxygen, a human may experience impaired respiration that may cause heart damage, nausea, and vomiting. Oxygen levels below ten percent may lead to an inability to move, loss of consciousness, convulsions, or death.

Accidents involving nitrogen occurred both in confined spaces and in “open” areas, according to the safety board, including both inside buildings and outdoors.

The board’s bulletin recommends careful handling and training around the storage and use of nitrogen, particularly in workplaces, including implementing warning systems and continuous air monitoring, ensuring proper ventilation, and planning ahead for the safe retrieval of those impacted if something goes wrong. Even simple precautions like color-coding and properly labeling gas tanks are important to preventing inadvertent mix-ups, according to the board.

It’s these types of safety measures that both guards and incarcerated individuals are concerned haven’t been taken by officials with the Alabama Department of Corrections.

Any lack of training or lapse of judgment could lead to disastrous consequences for the entire population of Holman, prisoner and staff.

“What if they go home one night and leave the gas on?” The individual on death row asked a Tread reporter.

“No regulation authority”

15 years after the deaths in the Delaware refinery, in 2021, tragedy moved south.

That January, six people, five men and one woman, ages 28 to 45 — Jose DeJesus Elias-Cabrera, Corey Alan Murphy, Nelly Perez-Rafael, Saulo Suarez-Bernal, Victor Vellez, and Edgar Vera-Garcia — died after nitrogen leaked into the Georgia chicken processing plant where they were working.

Four first responders, who arrived donning full protective gear, including respirators, were also hospitalized alongside more than half a dozen others.

In a preliminary investigation, federal regulators concluded the plant’s owners and the company who manufactured the liquid nitrogen equipment involved had failed to prevent the leak or train workers in responding to an emergency like the one that ended in the loss of six lives.

In both the Delaware and Georgia tragedies, as well as in dozens of other similar cases, federal agencies including the U.S. Chemical Safety Board (CSB) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) have moved quickly to investigate what happened, how, and what corrective actions involved parties could take to avoid similar accidents in the future.

Both federal and state officials have confirmed to Tread, however, that in Alabama, no such regulator — an entity concerned with the safety of state and local workers — has authority over the storage and planned use of nitrogen gas.

Tara Hutchison with the Alabama Department of Labor told Tread that the state agency has “no regulation authority” over gas storage and referred questions to OSHA.

“We have no regulation authority over gas storage, etc,” Hutchison wrote in an e-mail. “Alabama has no state-level agency – I would suggest you reach out to OSHA if they have any comment.”

In turn, a representative for the U.S. Department of Labor, of which OSHA is a part, said that the use of nitrogen — or any other gas — inside a state-run workplace is outside the scope of the agency’s regulatory authority.

“The Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) is a state agency, therefore OSHA does not have coverage over their work operations,” the representative said.

“It would kill us all.”

Alabama’s storage and use of nitrogen, then, will take place in a regulatory vacuum — an area outside traditional safety bounds. Its use of gas in state workplaces for the purpose of executions will go unregulated.

The man on Alabama’s death row warned that it’s a risk that could end in tragedy.

“We’ve obviously read about disasters in industrial settings with nitrogen that has given us pause,” he said. “It’s scary.”

And because Alabama is plowing forward with gas executions, he told Tread, everyone at Holman — both guards and the guarded — are on edge, anxious to see what comes next. It’s the stark reality of what could happen, not just to him, but to everyone inside the prison, that keeps nagging.

“The whole place could be flooded with nitrogen,” he said. “It would kill us all.”