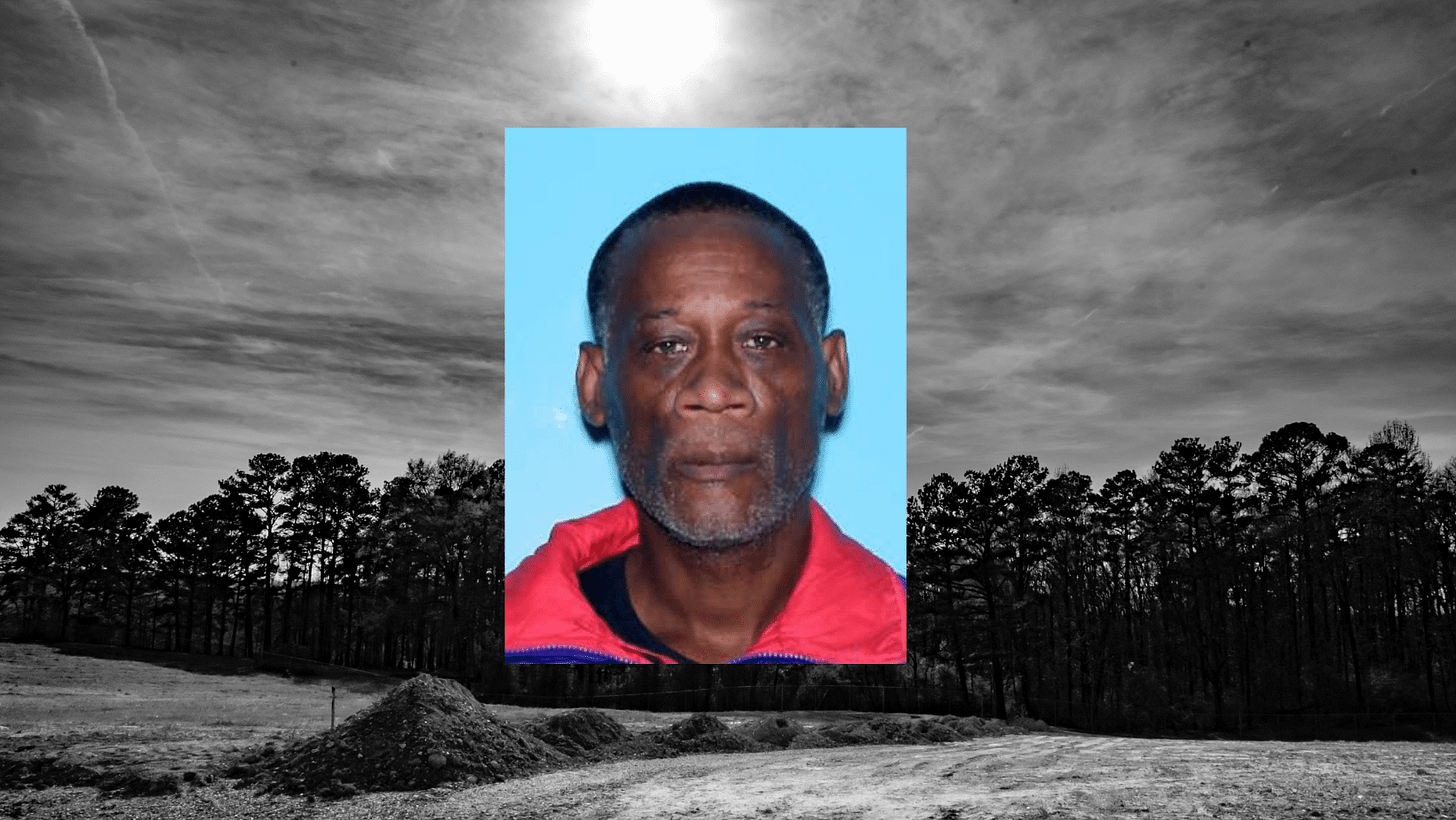

An Alabama hospital warmed him from 91 degrees and released him. 'Sweet James' froze to death the next day.

How James Effinger died of hypothermia outside a Birmingham Publix

An Alabama hospital warmed James Effinger from 91 degrees. Then he was on his own.

The 58-year-old had come to the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s emergency room that Friday because he was weak, according to medical records. Too weak.

When he arrived at the hospital, his body temperature was 91.2 degrees. James, who was facing homelessness and schizophrenia, was hypothermic. ER staff warmed him, records claim, and he “was released with instructions and directions for the nearby warming shelter.”

But that night — February 4, 2022 — there was no warming station open in Birmingham, according to both city and nonprofit records.

James Effinger was on his own.

Hours later, on the morning of February 5, 2022, Effinger died of environmental hypothermia outside a midtown Birmingham Publix.

Effinger’s death wasn’t an anomaly. He is one of at least four men who froze to death across Jefferson County, Alabama, in 2022. That marks a significant increase in hypothermia deaths in the county, according to records from the coroner’s office, which reflect as few as four exposure deaths in the entire decade prior to last year.

“Sweet James”

She called him “Sweet James.”

The nurse had known Effinger during her time working at a rehabilitation facility in Talladega, Alabama.

She read about his death on a local television station’s social media page. The coroner, she read, was asking for help in finding Effinger’s family. Officials had already figured out his name. They couldn’t miss it. It had been inscribed on his cane for all to see: James Effinger. But officials hadn’t yet found his loved ones.

The nurse didn’t know much about his family, either.

Still, she shared the post and a brief memory.

“Sweet James,” she wrote of Effinger. “He would get me when I walked through the door: 'Take me to the snack machine.’”

“Lord, I was just wanting to know the other day what happened to James,” another rehab worker commented. “And now I see this. It just breaks my heart.”

“Feeling weak”

On Friday, Feb. 4, Effinger went to UAB’s emergency room because he felt weak, according to medical records.

When he arrived at the ER on Friday, his body temperature was 91.2 degrees, dangerously far below the typical 98.6.

A review of hospital records by the coroner’s office showed that during his ER visit, Effinger had been warmed by UAB staff to normal body temperature, was medically evaluated, and was then “released with instructions and directions for the nearby warming shelter.”

The City of Birmingham, however, did not host a warming station the night of Feb. 4, according to city and nonprofit records. In fact, the circumstances of that night would not have triggered the city’s de facto warming station policy, which has been to only host a site if temperatures dip below freezing for consecutive nights.

City officials were already having difficulty finding a site for a warming station the following nights — Feb. 5 and 6 — according to a staffer at One Roof, the city’s lead homelessness agency.

A representative for UAB Hospital refused to answer specific questions about Effinger’s care for this story, citing federal privacy laws.

Into the night

In the end, James Effinger was on his own, and the temperature was beginning to drop.

By 9 p.m. that Friday evening, the temperature in Birmingham had already dipped to freezing.

And still, it crept lower.

Every hour after midnight, the temperature dropped another degree. By sunrise, it was 25 degrees in the Magic City.

Bundled and broken

When they found him, he was bundled up.

Birmingham 911 dispatch had received a call at 9:13 a.m. about an unresponsive man outside the Publix in midtown.

When they arrived, first responders found Effinger laying on the ground outside with his back against the wall. He wore a black windbreaker over a tan, long-sleeved shirt, and he wore jeans, a brown belt holding them up over a pair of blue basketball shorts.

Officials with Birmingham Fire/Rescue brought Effinger to UAB, the hospital where he’d been released the day before, according to coroner’s records.

When he arrived at UAB on the day of his death, Effinger’s body temperature was 78.4 degrees. Hypothermia — again.

Efforts to revive James were unsuccessful, and he was pronounced dead at 9:54 a.m.

At the time of his death, the temperature in Birmingham still hadn’t risen above freezing, and wouldn’t until that afternoon. City officials would open a warming station at 5 p.m. on Feb. 5 — more than 7 hours after Effinger froze to death.

One among many

Effinger’s death is not a solitary occurrence. In just over a decade, at least 8 men have frozen to death in Jefferson County, with four of those occurring in 2022 alone. Hundreds more people die each year across the country due to hypothermia.

Bill Yates, Chief Deputy Coroner of the Jefferson County Coroner/Medical Examiner’s Office, said that he can’t point to a single reason for the increase in hypothermia deaths, but that generally, those impacted by the weather tend to be those already at risk.

“They’re just more vulnerable,” he said. “I think we as a community should look at programs or efforts that can be made to help those people who fall into vulnerable situations.”

That may include funding mental health services, Yates said, which can ultimately help prevent many types of death.

James Effinger, for example, had a history of schizophrenia which may have left him susceptible to exposure to the cold, according to his autopsy report.

“Folks with mental illnesses may sometimes just be unable to make good decisions for their health and safety,” Yates said. “Not necessarily saying that somebody cannot recognize the cold as danger, but maybe even before that, just because of their mental health, they may not be able to establish a good support system or good housing, which makes them more vulnerable to other things — not just hypothermia but other things — like being a victim of a crime.”

Effinger’s death, too, brings into focus the logistics of when and where warming stations open in the city.

Dr. Marisa Zapata, an associate professor and director of Portland State University’s Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative, said policies about warming stations should be clear, transparent, and explained carefully to the community, including those who will be impacted the most by the policy – those sleeping on the city’s streets.

Those policies, she said, should also take into consideration circumstances like wind chill and rain. And if policies around warming stations turn out to be too rigid, she said, cities should engage with the opportunity to think more closely about the policy, its purpose, and its implementation.

“A good public policy is one that’s being constantly re-evaluated and questioned,” she said in an interview last year.

Buried by us all

Eventually, a representative of the coroner’s office was able to get in touch with a member of Effinger’s family, who told him that James would need to be buried by the county. A private burial wasn’t quite within financial reach.

In the end, then, the community where Effinger froze to death buried him — part of its legal duty to dispose of the dead, impoverished or otherwise.

There, at the county cemetery in Morris, James Effinger now rests among more than 8,000 others, indigent and unclaimed burials from years past. Each grave is marked with a number but no name.

Bill Yates said when he attends services in Morris, he thinks about the disconnect — the isolation that might have led to an individual being buried in a potter’s field.

“I usually think about the fact that the deceased is so disconnected from everybody — from friends, family, community,” he said. “And what led up to that? Why did that happen?”

Thank you. Even those who do not say so recognize the importance of these words.

An important article!