Camp Hill, Alabama, faced an undeclared disaster. Then came the Dadeville shooting.

How a small town was confronted with deadly gun violence and climate catastrophe

First, the hail came.

After, there was the water and its wake.

Then came the bullets.

The storm began before the sun had even risen on Sunday, March 26.

Soon, hail as large as grapefruits fell across Camp Hill, Alabama, a town of just over 1,300 people.

The hailstones ripped through roofs, through attics, and through ceilings, ravaging the homes of the city’s more than 90 percent Black population. In a town where more than one in three households experience poverty, nearly every home and business was damaged. Nearly every windshield in the town was shattered.

As the storm blew on, the water became the problem. First, of course, the water falling from above had been the primary concern. It poured through the places where the roofs of Camp Hill had utterly failed.

Sometimes, if a family was lucky, the water simply dripped slowly from the ceiling or seeped surreptitiously through the painted drywall. But other times — all too often, it seemed — the water fell through freely. Where shelter had been, for many, there was now only sky.

When the rain stopped, the problems didn’t. The water that stayed became the new threat. It soaked into carpets and walls. It wilted ceilings. And as it dried, the mold set in.

Then, the shots rang out.

On Saturday, less than a month after a hailstorm had torn Camp Hill apart, the community found itself reeling.

That day, at a Sweet 16 birthday party for his sister held in nearby Dadeville, Philstavious Dowdell, an 18-year-old from Camp Hill, became one of four teens killed in a mass shooting that left dozens more injured.

For many in Camp Hill, what was happening in their small Alabama town was the kind of loss and grief they’d never experienced before — an undeniable climate catastrophe quickly compounded by the stark, bloody reality of the impact of gun violence on their own community.

Now, in the days since the shooting and the weeks since the hailstorm, the residents of Camp Hill are aiming to survive, moving forward one day at a time. It’s what they said they’ve always done.

Still, a little help, residents and volunteers explained in interviews this week, could certainly go a long way.

Of hail and heartbreak

They knew the storm was coming. But they didn’t know the harsh truth of what would come with it.

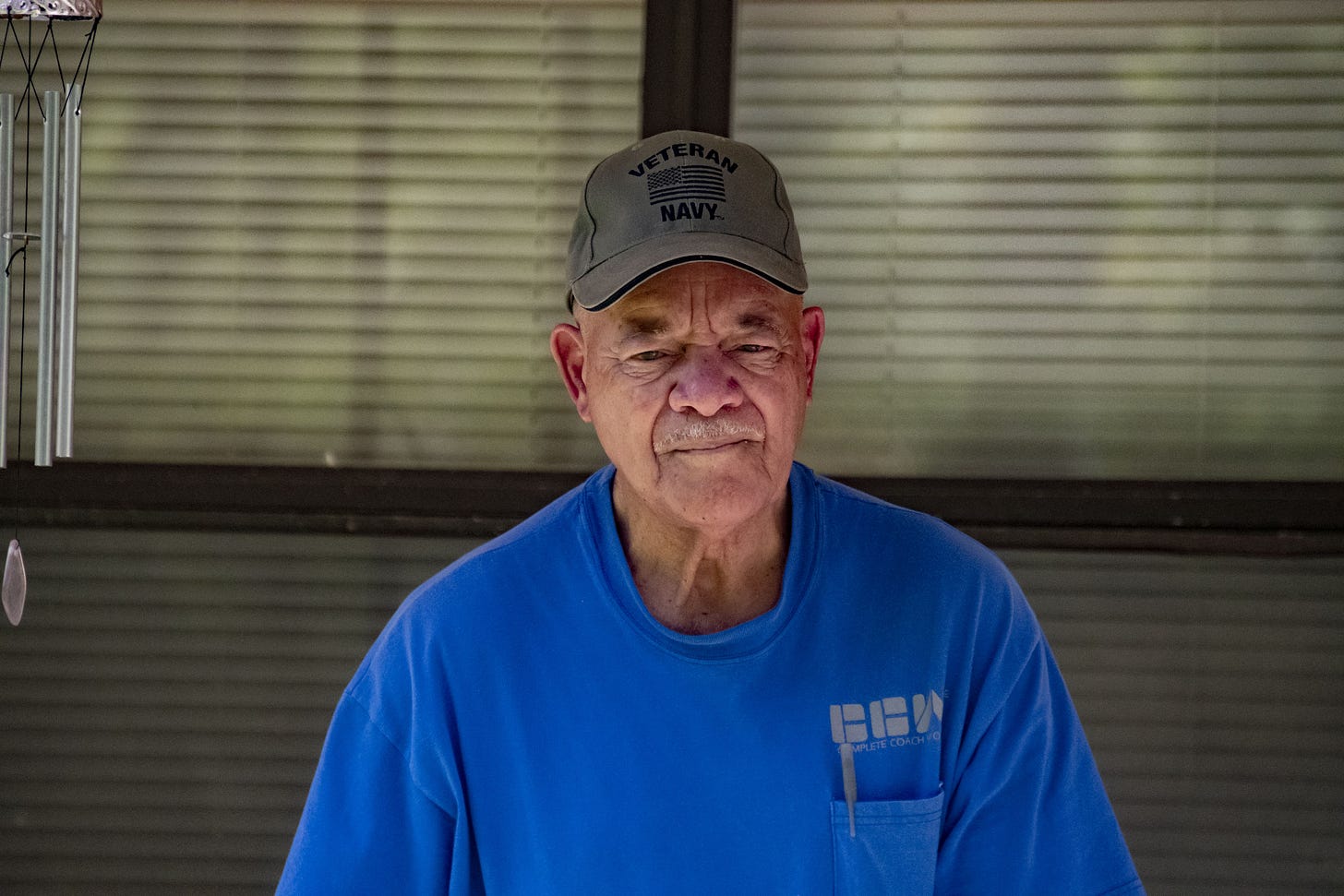

Red Walton was asleep when the hail began to fall. A Navy veteran, Walton grew up in Camp Hill. He spoke with Tread about the hailstorm on his 87th birthday, a slice of leftover birthday cake still sitting on the table in front of him.

“I got up and came down the hallway and heard a boom like a bomb went off,” Walton said.

He didn’t know yet, but a hailstone had pierced his roof.

“Then the water started dripping,” he said.

Walton immediately began to worry about how he would fix the problem. His granddaughter had planned to visit soon — to sleep on the bed that now lay beneath a leaking ceiling.

The slow leak wouldn’t be the last of Walton’s problems.

Chase Alexander was in the Camp Hill Volunteer Fire Department’s station during the storm. A Louisianan by birth, Alexander said he’s seen the devastation a natural disaster can wreak on a community. But what happened that Sunday was different, he said.

“We all got into a doorway of the station — that’s how bad it sounded,” Alexander explained. “We were scared.”

Soon, the fire station’s skylights had begun to pour water. The reality of the damage caused by the storm was starting to sink in.

Then, when the storm was over, the devastation became painfully apparent.

Dean Bonner, a local Coast Guard veteran with disaster response experience, said that what happened that Sunday was a uniquely catastrophic event.

“In a lot of homes, the hail went through the shingle, the plywood, and the ceiling and hit the floor,” Bonner said. “The hail came through metal carports and totaled cars. I’ve never seen or heard anything like this before.”

Once the rain had stopped, Red Walton, too, was about to see something he’d never seen before. He was sitting in his living room watching Gunsmoke, the sun shining outside, when he heard another boom, he said. It had sounded like the hail from the night before.

“All of a sudden a bomb went off down the hallway,” Walton said. “I wasn’t prepared to see what had happened.”

He walked back to the room that, the night before, had just been leaking. The ceiling over his guest bed had now collapsed completely.

“What the hell am I going to do?” Walton asked himself.

“Everything was wet”

For one Camp Hill mother, just up the road from Red Walton’s, the hailstorm changed everything.

The 38-year-old, whose name Tread has chosen to withhold, said she’s lived in Camp Hill all her life. She’s mom to two boys, ages 10 and 11.

The mother was at Kwangsung, a car parts plant in nearby Dadeville where she’s worked for 13 years, when the storm hit. Her shift ended at 7 a.m., and when she arrived home, what she saw broke her heart.

Her home had been devastated. Her partner and two sons had ridden out the storm inside, quickly moving to the living room after the roof had failed in the bedrooms. The hail had sounded like glass bottles being thrown at the roof, her family told her.

“When I got home, I seen all this,” she said, gesturing to the inside of her home. Around her, the impact of the storm was undeniable. The ceiling, first wet with rain, then dried by the Alabama heat, was rippled like a washboard throughout the home. In most rooms, mold was evident on both the ceiling and the walls.

“Everything was wet,” the mom explained. “My floor was wet. My children’s clothes were wet. My bedroom is still wet.”

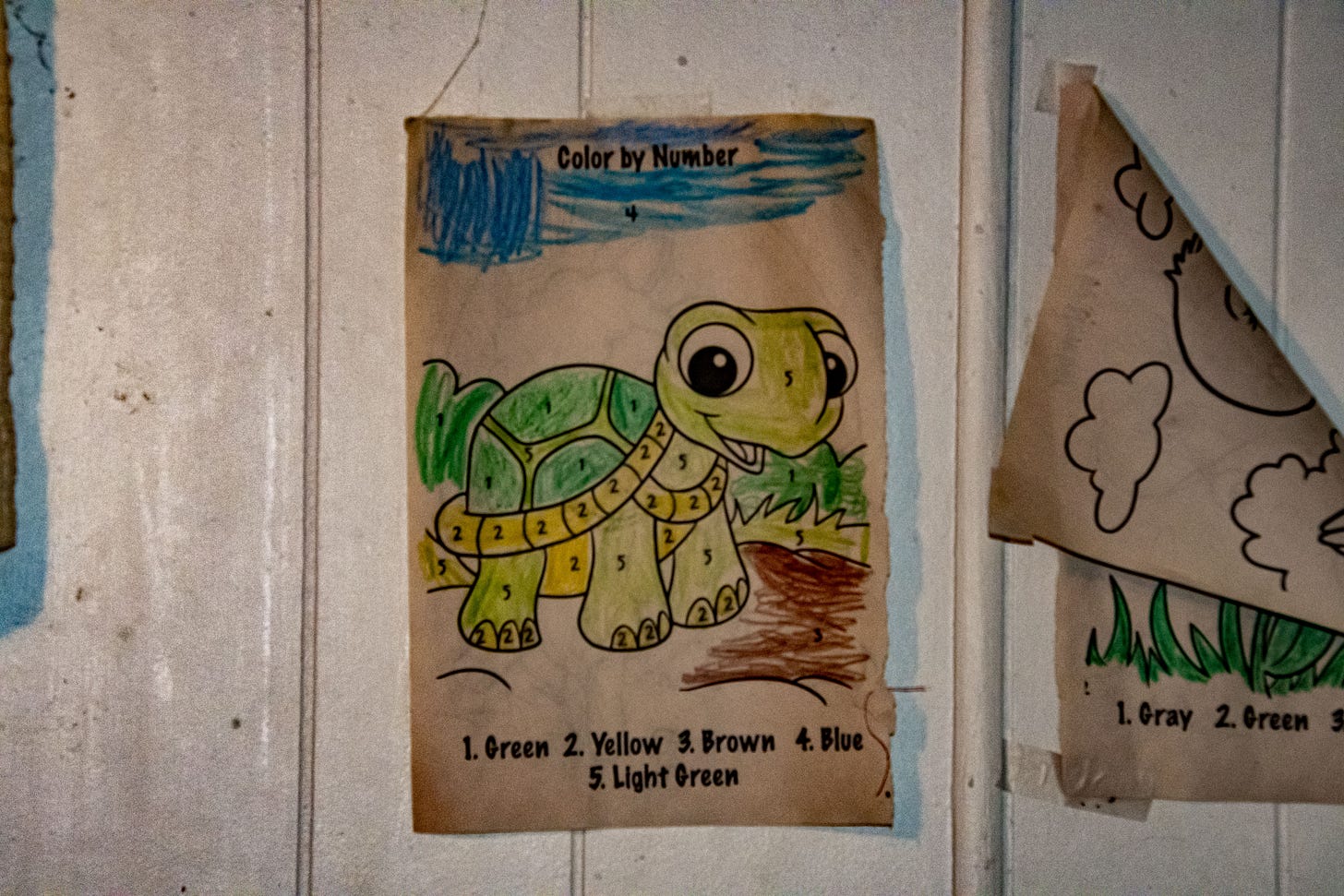

On the ceiling of the children’s bedroom, the mold’s black and green had already spread out starkly against the white popcorn background, dimly lit by a single, bare incandescent bulb. Below, the walls were adorned. An award for A/B honor roll. A turtle from a coloring book. A certificate of achievement for leading the pledge of allegiance.

Everything in the mother’s bedroom was blue — the sunshine pouring through the tarp put on by local volunteers. The thin blue plastic was the only thing left keeping the inside from the outside.

The mother said she needs help.

“We have to sleep on the couches,” she said. “It’s making my back hurt every night. And they want to be in their bed, just like I want to be in mine.”

She paused as she looked around. “But we really can’t.”

The mother said what happened in Camp Hill is a disaster and that she believes her family and others like it deserve help. Her mobile home, which was inherited by her partner, wasn’t insured, leaving the family with few options.

“This is my first time ever being through something like this,” the mother said. “It’s been tough.”

Each of the residents interviewed by Tread for this story characterized what happened in Camp Hill as a disaster. As of this writing, however, neither the state nor federal government has declared what happened in Camp Hill a disaster — a move that would result in the disbursal of much-needed government dollars to help cover the short and long-term costs of recovery.

And March’s hailstorm wasn’t the only disaster in store for Camp Hill.

“It still hurts”

Less than a month after the storm, Camp Hill’s Phil Dowdell, a senior bound for Jacksonville State University, was shot to death at his sister’s Sweet 16 party in Dadeville, a neighboring town where Camp Hill’s children attend school. Three others — Shaunkivia Nicole Smith, 17, Marsiah Emmanuel Collins, 19, and Corbin Dahmontrey Holston, 23, were also killed, according to the local coroner. Dozens more were injured, state law enforcement said.

Phil Dowdell lived down the street from Valerie Farrow’s mother in Camp Hill. She wore a Dadeville High School spirit shirt as she remembered the teenager Tuesday morning.

“If he walked up right now, he’d come give me a hug,” Farrow said. “He was always so nice and so respectful.”

Farrow’s niece was at the Sweet 16 party where the mass shooting took place. When they heard the shots ring out, she and her friends had piled themselves into a single bathroom stall in the dance studio where the party had been held.

The group waited. Moments later, someone banged on the door. One of the girls eventually cracked it, her niece said. It was a man with a gun. Though he didn’t identify himself, the man asked if the girls were okay and told them to leave. The group took off running, according to Farrow’s niece. On their way to the exit, they stepped over the bodies of their friends. Her niece, Farrow said, got blood on her shoes.

She breathed deeply as she continued.

“She wouldn’t go to school yesterday,” Farrow explained.

Even before the shooting happened, Farrow said she’d felt lost. Her uncle had recently died, she explained, and her house had gotten significant damage from the hailstorm.

The chunks of ice had made Swiss cheese of her siding. Several windows were broken — windows Farrow explained she’d had to pay for one at a time. Her roof, too, which she’s recently gotten a loan to finance, was dented every few inches from one corner of the home to the other.

Despite the challenges, she’d felt the city was headed toward recovery. Then came the shooting.

“I’m still hurt,” Farrow said. “I’m sad. I’ve been crying a lot these days.”

Disaster doubled

Warren Tidwell, Camp Hill’s community resilience coordinator, said he’s not aware of a place that’s faced such a devastating combination of disaster and tragedy in such a short time.

A self-described redneck who grew up in similarly rural Walker County, Alabama, Tidwell has been helping to facilitate volunteers and city workers’ disaster response in the weeks since the hailstorm.

So far, that effort has involved assessing storm damage, talking to local residents, revamping the local food pantry, and working to tarp as many roofs as possible to prevent further damage. But Tidwell said the resources to address the crisis appropriately just aren’t there. Skilled volunteers, for example, have been difficult to find — volunteers with the ability to, for example, tarp a roof or assess structural damage to a home or business.

Still, Tidwell said the folks on the ground in Camp Hill, however few, have been invaluable.

Amanda Casaday is one of those invaluable people, Tidwell said.

She’s been in Camp Hill working alongside her partner Josh Darling since he took over as chief of the town’s volunteer fire department last year. She said she’d felt that Camp Hill had been on the road toward recovery before the Dadeville shooting brought the community back to its knees.

“We were kind of getting back to semi-normal,” Casaday explained. “People were starting to get back to work — living their lives. But this happens in Dadeville, and it kicks you in the gut all over again. We had a weather disaster, and now we had this manmade disaster. When is this town going to get a break? When is enough enough?”

Keith Williams is another resource for Camp Hill. He said Wednesday that he’d never even heard of the town before Tidwell and others had helped to highlight the uphill battle its people were facing in the wake of the March hailstorm. When he found out volunteers were needed, he traveled from Birmingham to help.

Williams, an Army veteran, is setting up a small radio station to help provide residents with information about disaster relief efforts. He also has a higher aim, too — to improve the town’s morale.

“When you look around and you see the devastation, it can bring about desperation and depression,” Williams said. “But when people see there’s someone that actually cares — that there’s something actually happening in their town — that can alleviate some of that."

Williams said that help need not come solely from the community, though. Instead, he said, both the state and federal governments should declare what happened in Camp Hill a disaster and immediately act to mitigate the harm done by the hailstorm and its aftermath.

The delay in the issuance of a disaster declaration, Williams said, is shameful. Many factors — race, class, the simple fact that this was a hailstorm and not, say, a tornado — may play a role in the delay, Williams argued, but the reality on the ground is clear. What happened that Sunday was a disaster, and Camp Hill’s residents deserve all the help they can get.

“Don’t ask me what I’ve seen”

Josh Darling, Camp Hill’s fire chief, wasn’t eager to talk Wednesday afternoon. He sat silently in the disaster recovery command center, typing up notes from earlier that day.

In addition to his role in responding to the March hailstorm and the recovery that followed, Darling was one of the first officials to respond to the mass shooting in Dadeville.

“If you want to ask questions, fine,” Darling told Tread. “But don’t ask me how I am. Don’t ask me what I’ve seen. I have no use to talk about that.”

Originally from Georgia, Darling, a veteran of the Army National Guard, moved to Alabama to be with his partner, Amanda, eventually ending up as chief in Camp Hill last year.

Darling said he could have never predicted he’d be coping with a climate catastrophe and a mass shooting in just the first year on the job.

“What happened was a senseless tragedy,” he said of the Dadeville shooting. “We were rallying around the community to rebuild from a hailstorm. Now we need to rally around these families to rebuild their lives.”

An undeclared disaster

Darling said it’s difficult for him to understand why there hasn’t been a disaster declaration for Camp Hill.

“FEMA dropped the ball on this one,” the fire chief said. “Just because there was no tornado doesn’t mean this wasn’t a category-five disaster. Is it because we’re only nine square miles — is that why you’re not looking at us? Is it because we’re a primarily Black community? Is that it?”

In the end, though, Darling said the reason for the delay isn’t important. Action is what’s needed now.

“Just send help,” he said, frustration apparent in his voice. “People need help.”

The Camp Hill mother felt the same.

She said she recalled President Joe Biden's visit to Selma, Alabama, just weeks before the March hailstorm ravaged her home. She’d seen it on TV. He’d gone to commemorate Bloody Sunday and to extend a message of solidarity in the wake of Selma’s own natural disaster, a tornado that had flattened homes and businesses across the historic city.

President Biden, the mother said, should know about the conditions in her Camp Hill home: conditions that, so far, the government has said don’t amount to a disaster.

“We’ve been trying to get people to help us fix it,” she said. “But I really don’t have the money to do anything.”