Charles "Sonny" Burton killed no one. Alabama plans to suffocate him anyway.

Jurors, the victim's daughter and Burton's family believe his life should be spared. The state thinks otherwise.

Sonny Burton can no longer walk.

His loved ones worry that, should the time come, prison staffers will have to roll the 75-year-old into Alabama’s execution chamber on a gurney. One final indignity, they say, for a man the state admits never killed a soul.

And sometimes Eddie Mae Ellison worries that her older brother, Charles “Sonny” Burton, is already fading away.

Wheelchair bound and suffering from debilitating rheumatoid arthritis while living on Alabama’s death row, he can no longer move at all without a significant amount of pain.

“Help me!” He scrawled on a medical form to prison staffers in 2024.

“I feel misery,” he wrote on another form in January 2025. “Please help.”

The degenerative disease, which affects most of his body, limits his mobility and often leaves him in unbearable pain.

“It feels like somebody taking a knife and sticking it between your joints and trying to pry your joints loose,” Burton said.

Among the things that bother him most: he can no longer get on his knees to pray.

The Department of Corrections has provided him a helmet to limit his risk of falling: a protective measure ahead of the state’s planned attempt to put him to death.

In January, the Alabama Supreme Court paved the way for the Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey to set Burton’s execution date.

Burton’s body is already failing him. Soon, barring court action or clemency, Alabama will execute him anyway.

Eddie Mae Ellison said she fears her brother’s days are already numbered, but she says the state doesn’t deserve to take away what time he has left.

Burton already calls his family less and less often. When they do speak, he’s sometimes hard to follow.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Ellison said. “Because mentally, he’s drifting away.”

But even in the shadow of the state’s effort to push forward with her brother’s execution, Ellison and those who know Burton are holding on to hope. It’s all they have.

On Thursday evening, Ellison sat in the front row of Montgomery’s Capri Theatre as her brother’s voice echoed around her. Burton’s family and legal team flanked her, all gathered in the state’s capital for the screening of a film documenting Burton’s case for reprieve from Alabama Governor Kay Ivey.

For more than three decades, Burton has served on Alabama’s death row for his role in the 1991 robbery of a Talladega AutoZone. During the robbery, one of five people who’d arrived with Burton, Derrick DeBruce, shot and killed Doug Battle, a customer who’d walked into the store.

Burton admits that he was one of the men who participated in the robbery, but no one—including the state—disputes that Burton did not kill Battle. Testimony in the case showed that Burton wasn’t inside the building when the fatal shot was fired.

“Not only did he not kill anyone, but he didn’t order anyone to kill anyone,” said Matt Schulz, one of Burton’s lawyers. “He didn’t hire anyone to kill anyone. He didn’t tell anyone to kill anyone. He literally did not even see anyone kill anyone.”

Jurors, victim’s daughter oppose execution

More than three decades after the crime and Burton’s conviction, nearly everyone involved in the case—with the apparent exception of state prosecutors—believes that Burton’s life should be spared.

Six of eight living jurors who voted to sentence Burton to death now say justice would be better served if the state spared his life. Three have explicitly asked Gov. Kay Ivey to grant Burton clemency.

Priscilla Townsend said she was young when she was a juror on the case all those years ago. In a letter to Gov. Ivey, she said her view on the case has changed.

“It didn’t sit right with me that someone who had not pulled the trigger was sentenced to be executed, and my heart went out to him,” she wrote.

If executed, Burton would be the only of the six participants in the 1991 robbery to be put to death for the murder. All six were charged with capital murder, but most pleaded to lesser charges to avoid the death penalty. Only Burton and DeBruce, the gunman, were sentenced to death. DeBruce’s capital sentence was ultimately overturned by a federal court, after which he was resentenced to life without parole, allowing the shooter to avoid the death penalty with the state’s approval.

“I do not see how this execution will contribute to my healing.”

-Tori Battle, daughter of murder victim Doug Battle

Another of the jurors who sentenced Burton to death, James Cottongim, said that while nothing will truly make up for Battle’s murder, executing Burton doesn’t seem just.

“Mr. Burton was not the man who pulled the trigger,” Cottongim wrote. “It just seems wrong that he should be put to death when the shooter was resentenced to life… Our original sentence of death is just no longer appropriate given the circumstances.”

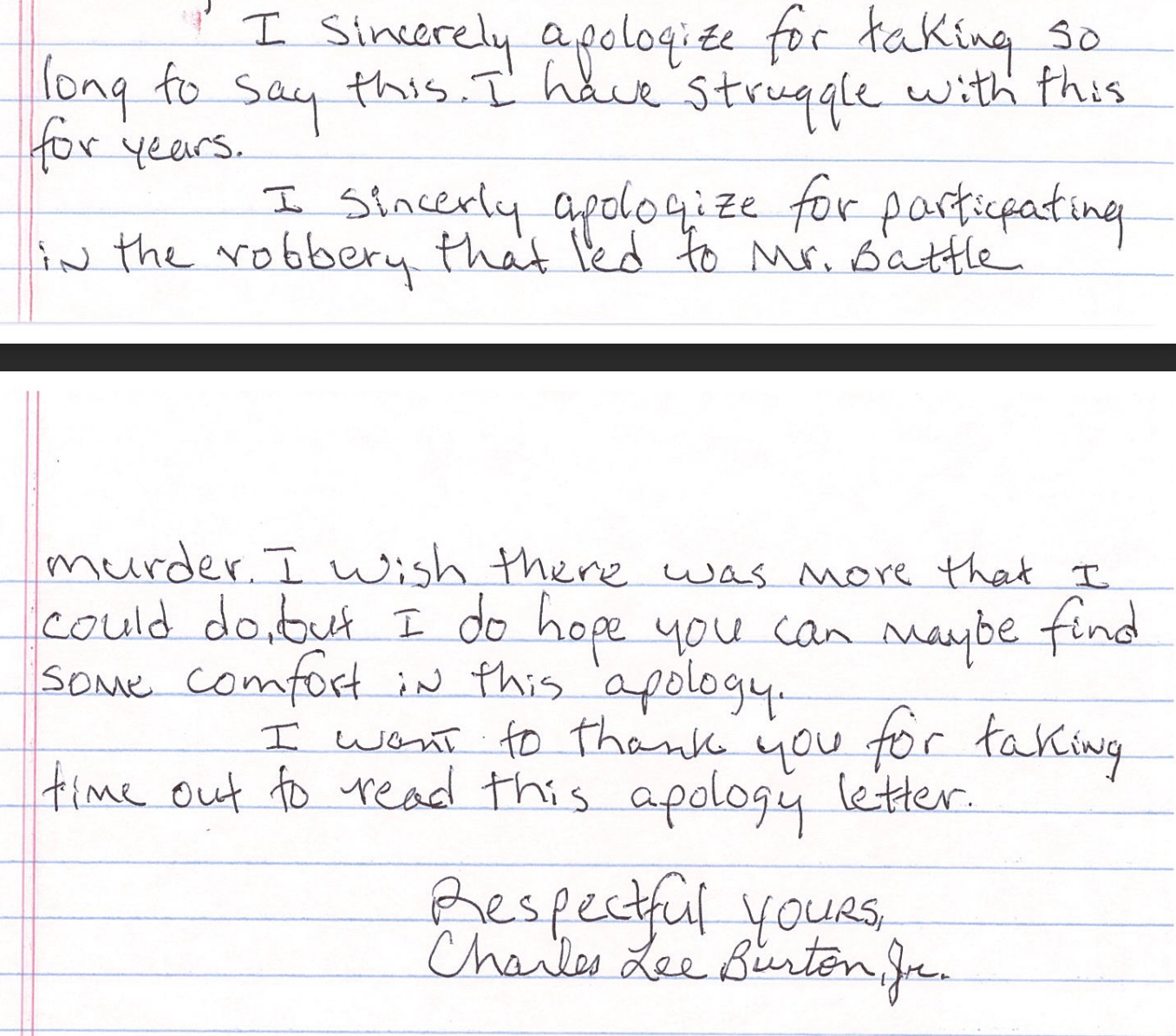

Burton has apologized to the Battle family.

“I sincerely apologize for participating in the robbery that led to Mr. Battle’s murder,” he wrote in a letter to Battle’s loved ones. “ I wish there was more that I could do, but I do hope you can maybe find some comfort in this apology.”

Doug Battle’s daughter Tori opposes Burton’s execution. She wrote a letter to Ivey advocating on behalf of the man condemned to die for her father’s murder.

“I do not see how this execution will contribute to my healing,” Tori Battle wrote in part. “My father, Doug Battle, was many things. He was strong, but he valued peace. He did not believe in revenge. And in that way, I am very much his daughter… I hope you will consider extending grace to Mr. Burton and granting him clemency.”

Life and Death in Dixie

If Burton’s execution were to move forward, Ivey, a Republican, will have presided over the execution of 26 people during her 9 years as governor, the most of any state executive since the death penalty was reinstated nationally in 1976.

Ivey presided over a three-month execution moratorium in the state following correctional staff’s repeated failure to execute condemned men by lethal injection. Following the end of that moratorium, Alabama became the first state in the U.S.—and the first government anywhere—to put a condemned man to death using nitrogen suffocation.

Clemency is rare in Alabama, a deep red state where a “tough on crime” stance is often seen as a political necessity.

But in March 2025, Ivey became the first governor this century to grant relief to a resident of death row when she commuted Rocky Myers’ capital sentence to life in prison. Ivey said the decision was “one of the most difficult decisions I’ve had to make as governor.”

Schulz, one of Burton’s attorneys who’s known him for 17 years, understands that obtaining clemency from any Alabama governor is a long shot, but he said the pardon power exists precisely for cases like this.

“This outlier case is a quintessential case for the exercise of executive clemency,” Schulz and Burton’s legal team wrote in their appeal to Ivey. “It is one which, similarly to a handful of cases from other states, slipped through the cracks.”

The case represents a “cascade of failures,” both legal and moral, Schulz said, and deserves intervention from the governor.

A Wardrobe and a Wish

Burton was raised in Montgomery in the shadow of Jim Crow. Throughout his childhood, Burton suffered abuse at the hands of his father. By age 14, he had already run away from home multiple times to avoid abuse.

Ellison, who lived with Burton’s biological mother and her father, recalled how as a child, Burton had showed up at the home and asked his siblings to hide him.

“His daddy had beat him so bad,” she recalled.

Ellison helped the boy into the bottom of a wardrobe, where he stayed for three days. Only when pushed by their parents did the other children finally reveal Burton’s hiding place. As the adults pulled him from the wardrobe, Ellison put her head down and avoided her brother’s eyes. She worried what would come next.

“That was the first time in my life and the only time in my life when I couldn’t look him in his face,” she said. “Because we had let him down. And whatever happened was going to be our fault.”

Burton begged to stay.

“I want you to be my daddy,” he told his stepfather.

Ellison said she feels that was the beginning of the end for Burton—an inflection point after which nothing would be the same.

Before long, she said, her brother would begin making decisions that would ultimately lead him to that Talladega AutoZone in 1991.

What happened that day, Ellison said, was the culmination of many bad choices by Burton, though none of them should cost him his life.

A Lesson in Mercy

Burton and his family know about mercy. After he was incarcerated, Burton’s first wife was murdered alongside her partner. Eventually, Burton would forgive the killer and urge his family to do the same.

“My father asked me to forgive,” Burton’s son, Charles III, said. “My father has gotten very wise in his years.”

His wife’s murderer, Larry Green, would eventually be sentenced to life in prison, not the death penalty, for the double homicide—an irony not lost on Burton’s family.

“You ain’t even killed nobody,” Carolyn Shavers, Burton’s daughter, told him on a recent call. Shavers found her mother’s body after the murder. “But that man killed my mama.”

Thursday’s screening at the Capri was an opportunity, the family said, to show the world what they already know: Sonny Burton is a light, they said. A light that deserves to keep on shining.

The men on Alabama’s death row already know that. Burton has become like the community grandpa at Holman prison, according to Nancy Palombi, a paralegal and investigator who’s known him for two decades.

When Burton was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, doctors told him he would likely lose his ability to walk. The men on the row weren’t having it, according to Palombi. One man in particular, Carey Grayson, told Burton to hold onto hope. Grayson reached out to Schulz and asked that he send in physical therapy materials so that he could help Burton find some relief.

It’s those simple gestures that show what Burton means to the men, many of whom have now lived with Burton for more than 30 years.

The State of Alabama executed Carey Grayson in 2024.

Ultimately, Burton’s family, many of his jurors, and Tori Battle, who lost her father, believe that granting Sonny Burton clemency is simply about doing the right thing.

“My daddy, who never killed anyone, is on death row,” Shavers wrote in a letter to the governor. “Please don’t let them execute him. He is my whole heart.”

“My dad…has paid the price for the crime he committed—robbery,” Ann Bradford-Harris wrote. “Please do not take my father’s life for the choice the Mr. DeBruce made.”

“I am a better man because of the way my father has guided me in the last 34 years since his sentence,” Charles Burton III wrote. “I ask you to spare his life… I love my father, and I just want him around.”

Toward the end of Thursday’s gathering, Schulz read a statement from Tori Battle, who couldn’t make it to the event.

“I wish I was there,” Battle wrote.

Tears filled Ellison’s eyes.

“This is a special moment for not only his family but for me, too, as the victim’s daughter,” the statement continued. “I want to extend my prayers to him and his family as they go through this process… I have voiced my opinion to Governor Ivey. I hope and pray she does the right thing and does not allow this execution to go forward.”

Thank you from all of us of Project Hope to Abolish the Death Penalty

Thank you for your good work of sharing these stories.