A far cry from freedom: 591 days of Alabama solitary

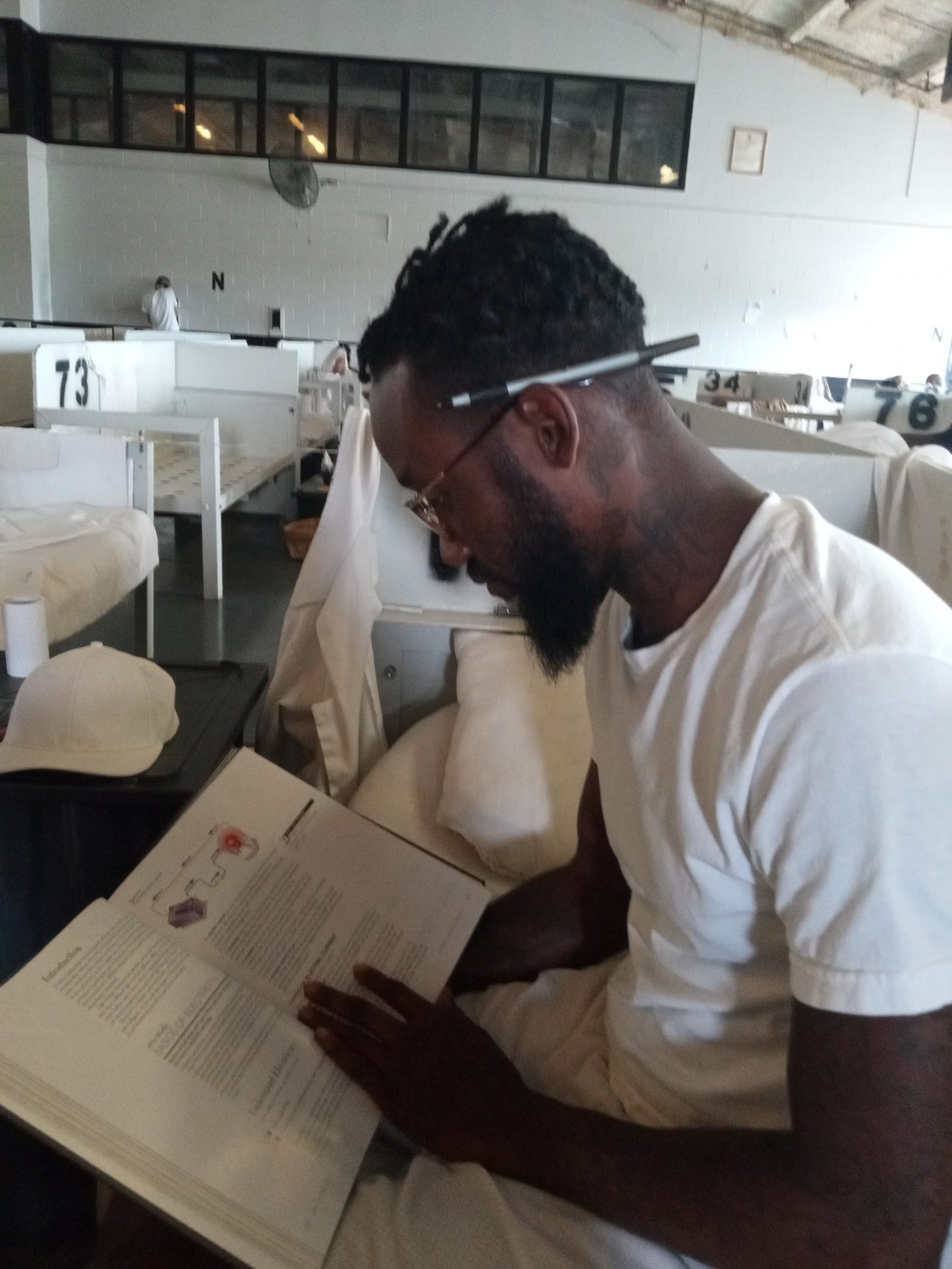

Donderrious Williams has spent most his life at the hands of the state. He refuses to be its victim.

He prayed for help.

Donderrious Williams was already doused in pepper spray as eight Alabama prison guards dragged him out of his cell, shackled him, and slammed his head onto a table, he told Tread. Praying was all he could think to do.

“I asked God to help me,” Williams, now 37, said in an interview.

For nearly 30 years, from foster care to the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC), Williams’ life had unraveled at the hands of the state. Now, Williams said he’s refocused on his commitment that he will not be its victim.

This week, Donderrious Williams filed a federal lawsuit against correctional officers and other ADOC officials, including Commissioner John Hamm, alleging that their actions have violated his rights under the U.S. Constitution.

In a 32-page suit filed Friday, lawyers for Williams allege that prison workers subjected their client to excessive force to curb his right to religious expression, repeatedly used near-freezing temperatures as punishment, and subjected Williams to solitary confinement for a torturous 591 days. ADOC staffers also destroyed legitimate legal mail, even claiming Williams had someone pose as a lawyer, limiting the man’s ability to have adequate legal representation, the complaint says.

Ward of the state

Donderrious Williams will never forget.

At five years old, he watched as police officers kicked in the door of his Ensley, Alabama, home and took his mother away over drugs.

It was Williams’ first interaction with the state — a government in the Heart of Dixie that would take him into its custody — first as a foster child that day, then, over a decade later, as its prisoner.

“It gives me a sense of insecurity. I could never have a sense of being complete or being confident at all. It always went back to the beginning.”

It was after that first interaction, as Williams passed from foster family to foster family that he first really got to know the state. Some families, Williams told Tread, treated him as “their own flesh and blood.” There were others, he explained, that saw him as a reliable source of income, not a person. And then there was the sexual abuse. All while in the “care” of the state.

“And no matter how much a family loved you or embraced you, there was always a void in the back of you your head,” Williams said of his experience in the Alabama foster care system. “It gives me a sense of insecurity. I could never have a sense of being complete or being confident at all. It always went back to the beginning.”

Back to the beginning

Not long after Williams aged out of the foster system, his brother Ronald was shot and left for dead during a 2005 carjacking in Birmingham.

Later, according to prosecutors in Williams’ trial, Donderrious shot and killed Bryan Lewis, a man who he believed had stolen a phone from his brother as he lay bleeding in the street. Williams argued that another man, Anthony Thompson, was the shooter, but a jury convicted Williams anyway, sentencing him to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Once again, Williams found himself back in the state’s grasp.

Now, Williams has served more than 17 years in Alabama prisons. Soon, the amount of time he’s spent in prison will eclipse the time he spent in Alabama’s care as a child.

“This is slavery”

The abuse, verbal and physical, started immediately, Williams told Tread. He’s still struck by his first thought as he stepped off the bus to be “introduced” to prison years ago.

“This is slavery,” he remembered thinking. “I called my mama, and I said ‘I have experienced what my ancestors experienced.’ That’s how serious it was.”

In the years since, Williams said his life at the hands of the state has met that grim expectation.

Williams said when he was transferred to Limestone Correctional Facility in 2018, Lieutenant Jeremy Pelzer set the scene for what was to come. That December night, Pelzer asked Williams if he was in a gang. Williams said no and asked why the officer would think he was.

“Because you’re black,” Pelzer replied, according to Williams.

Williams said Black individuals inside Alabama prisons are systematically treated worse than their white counterparts.

“Being Black in prison in the State of Alabama, you are stereotyped,” Williams said. “You could be walking down the hall, you will be looked at as a troublemaker — like you’re up to something.”

591 days of solitary

In 2021, while still incarcerated at Limestone, Williams was attacked by a cellmate, according to the federal complaint.

“On March 5, 2021, Mr. Williams’s cellmate, in a state of drunken confusion, attacked Mr. Williams in their cell,” the suit says. “There were no correctional officers in the immediate area to protect Mr. Williams, leaving him to de-escalate and stop his cellmate’s attack himself. In so doing, Mr. Williams cut his cellmate’s arm.”

In response, a correctional lieutenant took Williams to an outdoor holding cell, where he left him for more than an hour dressed only in a t-shirt and thin pants, according to the suit, leaving him “unable to speak from apparent hypothermia.”

The low temperature overnight was 38 degrees, according to the National Weather Service.

In the days that followed, Williams was charged with rules violations over the incident. His cellmate, according to the lawsuit, repeatedly said Williams wasn’t to blame for the injury, but prison officials did not allow him to testify.

What came after, Williams explained, was 591 days of solitary confinement. In an interview, Williams called the practice torture.

“I took a razor, and I broke it, and I opened it.”

“Solitary confinement is a place where you have to be mentally strong,” Williams told Tread. “Even the guys who survive, we come out not right.”

Many men placed in solitary confinement already face mental health issues, compounding the isolation’s impact on those subjected to it.

Williams said he considered suicide during his time in segregation.

“I took a razor, and I broke it, and I opened it,” he said. “I look at myself in the mirror, and the only thing that stopped by from cutting my throat that night was my grandson and my daughters and how I would let my family down.”

Solitary confinement is torture, Williams said, and he lived it at the hands of the State of Alabama, he said.

The tale of Joseph Perkovich

About four months later, in July 2021, one of Williams’ former lawyers, Joseph Perkovich, sent him a copy of a court ruling he thought could potentially impact his case.

The priority mail envelope’s clear label — “LEGAL MAIL” — didn’t deter a prison official’s unfounded suspicions, according to Williams’ lawsuit.

A correctional lieutenant opened the envelope, inspected it, and destroyed it. The lieutenant, without retaining the alleged evidence or even testing it for the presence of drugs, claimed Williams had someone pose as an attorney to aid in smuggling a drug called “Flakka” into the prison. The pages of the court ruling, the lieutenant claimed, were dipped in the drug, and Joseph Perkovich simply didn’t exist.

“Mr. Perkovich certainly does exist,” Williams’ lawsuit asserts. “[He] had communicated with Limestone to secure approval for and schedule legal calls on several occasions prior to, and after, the destruction of his correspondence.”

While the official’s accusations were baseless, the suit claims, they led to an additional 75 days of solitary confinement for Williams and serious limits on his ability to be represented by counsel.

“Mr. Perkovich stopped sending legal mail to Mr. Williams or visiting Mr. Williams in person,” the suit explains. “Further, after obtaining legal advice from Alabama practitioners, Mr. Perkovich concluded an attempt to visit Mr. Williams…would seriously risk his wrongful arrest and prosecution.”

“They demoralized me”

For Donderrious Williams, the worst came just over a year ago.

In February 2022, prison guards began aggressively complaining about Williams’ hair, which Williams, a Muslim, had grown out for religious reasons.

His hair, he explained, is part of his connection to God — a means of religious expression.

“My hair is my personality,” Williams said.

Fearing for his safety, Williams contacted his attorney at the time, Mr. Perkovich, who contacted Lieutenant Pelzer at Limestone. Pelzer assured Perkovish, the lawsuit claims, that Williams would not be “contacted or removed from his cell” that night.

Despite that assurance, eight correctional officers approached Williams’ cell that night, informing him that he would be receiving a haircut regardless of his religious objections.

The guards sprayed Sabre Red, a riot pepper spray, into Williams’ cell in an effort to force Williams into compliance with their demands. Still, Williams peacefully refused, he said.

Then guards escalated the situation, he explained.

“They put me in shackles and handcuffs, picked me up, drug me across the floor, slammed my head on the table, held me in a chokehold, and just shaved my head like a little five-year-old playing with someone’s hair,” Williams told Tread.

As they held him down, Williams prayed for help. It was all he could do.

“They demoralized me in front of everybody and laughed about it,” Williams told Tread.

The assault left Williams bruised physically and mentally, he said. The forced cut left him bald in some spots and with untouched hair in others. After it was over, Williams said that officers once again placed him in frigid conditions, injured and shackled.

“I was denied the right to be a human being.”

“The officers left Mr. Williams handcuffed in his cell for several hours with no coverings on a Winter night with the temperature hovering around freezing, covered in burning pepper spray until the next shift change,” the suit alleges. “The assault caused Mr. Williams severe bruising across his body, particularly on his wrists, ankles, back, and face. They also caused several lacerations, which the pepper spray they refused to allow him to wash off entered and aggravated.”

Williams’ lawsuit asks the federal court to order Alabama prison officials to prohibit the spraying of pepper spray into locked segregation cells, prohibit the shackling of those exposed to pepper spray “for longer than reasonably necessary,” and to prohibit the chaining or other confinement of individuals who are exposed to “danger or pain” due to extreme temperatures or other environmental conditions.

The suit also asks for compensatory and punitive damages, reasonable attorneys’ fees, and a ruling declaring that ADOC employees’ actions violated the rights of Donderrious Williams.

Williams told Tread that as his suit against the state moves forward, he will continue to pursue justice for himself and others like him in the custody of the State of Alabama. He will continue to push back against what he views as one of the Heart of Dixie’s highest crimes: “I was denied the right to be a human being.”

The Alabama Department of Corrections has not responded to requests for comment on Williams’ claims as of this writing.